How spatial occupation affects the residents of the West Bank

by Shelly Rourke

If you look at world maps, you won’t find Palestine; it seems to have been erased, and the deliberate linguistic extermination of the word is evident. Instead, all that remains are the fragmented territories of the West Bank and Gaza.

Growing up singing Christmas carols, I became familiar with Bethlehem, only to realize that it is not just a mystical place existing solely in religious stories but a real city.

Prior to entering the West Bank, one cannot ignore the large red warning signs indicating that entrance by Israelis is dangerous and forbidden. Passing through the checkpoints, barrels of machine guns are pointed directly at the bus I’m a passenger on, ready to fire at any unexpected occurrence. Multiple soldiers in their 20s hover around the gated barriers and concrete pods, scrutinising the documentation of the people passing through.

Growing up singing Christmas carols, I became familiar with Bethlehem, only to realize that it is not just a mystical place existing solely in religious stories but a real city. The people living here are subjected to a dystopian reality, living under brutal military rule. They are observed by snipers, hindered by military checkpoints restricting their movement, and surrounded by the constant sounds of gunshots, keeping them in a perpetual state of fear. Facial recognition cameras subject them to discrimination, while AI-controlled machine guns ensure pinpoint accuracy if fired upon.

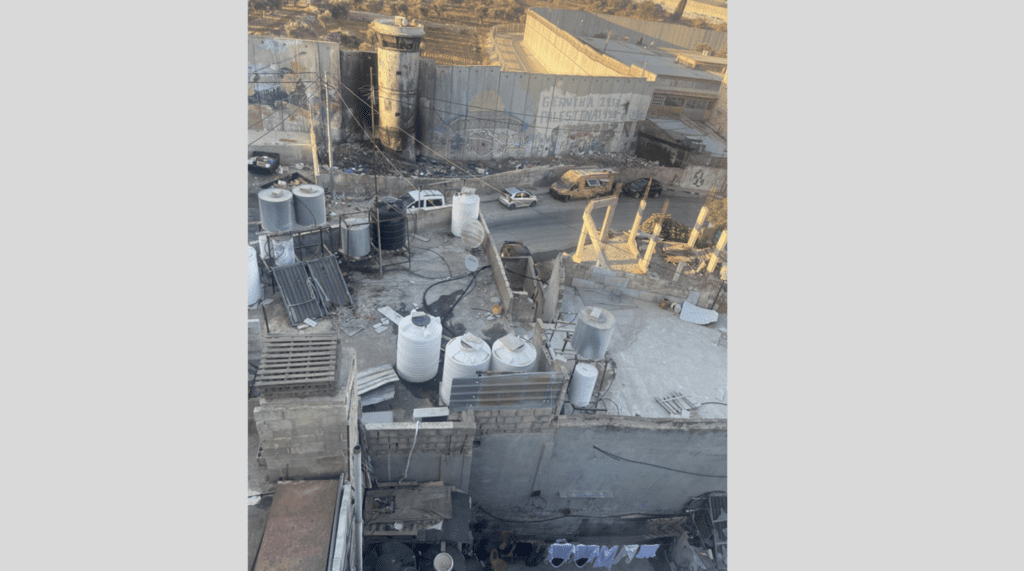

In August 2023, I arrived in Bethlehem, West Bank, to participate in an international camp at the Lagee Centre in Aida Refugee Camp. Aida is surrounded by a 9 metre tall wall made of precast panels that encircle and confine the community. Under the vigilant gaze of the Israeli military, watchtowers punctuate at irregular intervals along the apartheid wall, overseeing the 6,000 refugees, displaced since the Al Nabka (the catastrophe) of 1948. Ask any child in Aida about their origin, and they will instantly name their grandparents’ townlands, showing keys that no longer unlock any door. Following the initial tents of the 1950’s, the grandparents were given a 7sqm plot of land on which they built their home. As families expanded, each generation added a new floor. Reinforced steel bars pierce the rooftops, inviting the next generation to build upon them, resulting in a densely populated 0.5km².

Artists repurpose discarded metal into jewellery for tourists, who can narrate stories of visiting the most tear-gassed place in the world.

What remains of the West Bank is further gobbled up and reshaped by illegal Israeli settlements, continuously expanding and threatening existing Palestinian communities. These settlements are connected by apartheid roads inaccessible to Palestinians, further isolating them. Thousand-year-old olive trees are uprooted and placed near Israeli settlements to create an appearance of historical continuity. Contrary to the spacious Israeli settlements, with hundreds of flags, blue stars fluttering, Palestinian housing is densely packed, with water towers on roofs signifying a population controlled by others. Water flow is regulated by Israeli forces, unpredictable and necessitating storage for a constant supply.

I mounted the bus to Jerusalem only to be hit with a wave of emotion, what I stepped out of is a life under brutal occupation and it so far removed from the free reality we live in.

Hundreds of checkpoints infiltrate the West Bank, and sudden roadblocks imposed by the Israeli military paralyze movement. The military occupation distorts distances, compelling people to wait at road gates, borders, and checkpoints for permission to be granted. Soldiers interrogate Palestinians about their origins while they themselves stand on confiscated land. Complex routes circumnavigate Jewish settlements and Jerusalem’s suburbs, elongating journeys unnecessarily and confusing the region’s geography. Palestinians cannot guarantee arrival times, as these are subject to the soldiers’ mood at checkpoints, and disturbances in northern cities such as Jenin can affect movement in the south. Al-Aqsa Mosque, Islam’s third most holiest site, is a mere 7 km from Aida Refugee Camp, yet accessing it without an unattainable permit brands one a criminal. Along routes between various West Bank cities, Israeli settlers operate diggers and bulldozers, disfiguring the landscape Palestinians once carefully tended to.

Restrictive planning laws deny Palestinians the right to construct on their own land gradually forcing them out of their communities. This became evident in Beit Eskaria, a village between Bethlehem and Hebron, where settlements strategically perch on hilltops, ominously overseeing X below. In Israel, Arabic is no longer the official language and navigating the legal system without Hebrew exacerbates the complexities of the exclusionary planning laws. Here, Israel instantly demolished 35 new homes and a mosque, making it difficult for the community to sustain itself for future generations. All that remains are the remnants of the former building projects, serving as a gentle reminder that unlawful construction is a futile endeavour.

Thousand-year-old olive trees are uprooted and placed near Israeli settlements to create an appearance of historical continuity.

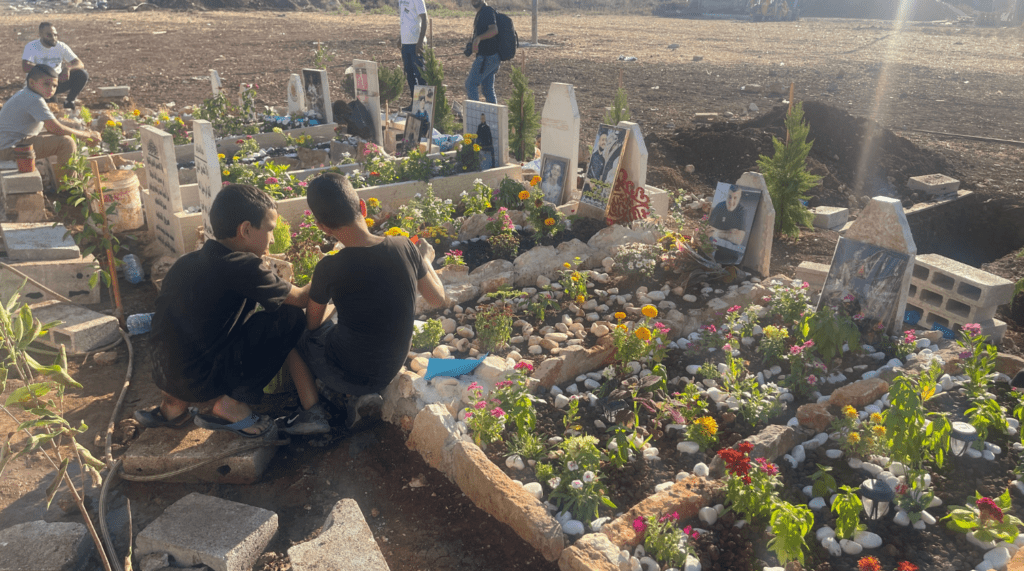

Cities like Jenin and Nablus defy military rule, and this results in every wall being adorned with countless images of male martyrs. In Jenin, roads have been purposefully destroyed, disrupting infrastructure, extending the time taken to undertake everyday activities and strategically impeding ambulances from reaching injured victims. A new cemetery, established on a recently flattened vast wasteland, has soil that is speckled with coloured rubbish and glass. Family members and friends sit beside fresh mounds, grieving for the young lives lost. Parents receive their excellent results of their murdered teenagers on the day of their funeral.

Returning to Israel (referred to by Palestinians as ’48), from Bethlehem, necessitates passing through Checkpoint 300. Depending on the time of day, the line may be dense with Palestinians holding permits to work in Israel. Once again, the Israeli military subjects them to waiting in spaces resembling milking stalls, tightly packed, scrutinizing their identity cards at a sluggish pace, degrading them at every possible opportunity. Before the turnstiles, signs in Arabic are mounted on the walls, emphasizing that the checkpoint was built for them and it was their responsibility to maintain its cleanliness.

Emerging on the other side, an advertisement announces that the metropolitan city of Tel Aviv is just a short one-hour distance away. I mounted the bus to Jerusalem only to be hit with a wave of emotion, what I stepped out of is a life under brutal occupation and it so far removed from the free reality we live in. I had the choice to leave, unfortunately for them, it is the only reality that perhaps they will only ever know. At the airports departure gates, the questioning fluctuated between the serious and the absurd, asking had you visited Bethlehem, Jenin, Nablus, and Hebron in the West Bank, knowing that a slip of the tongue would deny a chance of ever returning. The Israelis are the masters of the house and for now they determine everything.

About Shelly Rourke

No related posts.